Kirsh, D., ‘The Context of Work’, Human Computer Interaction, 2001

David

Kirsh

Dept of Cognitive Science

UCSD

Abstract: The question of how to conceive and represent the context of work is explored from the theoretical perspective of distributed cognition. It is argued that to understand the office work context we need to go beyond tracking superficial physical attributes such as who or what is where when, and consider the state of digital resources, people’s concepts, task state, social relations and the local work culture, to name a few. In analyzing an office more deeply three concepts are especially helpful: entry points, action landscapes, and coordinating mechanisms. An entry point is a structure or cue that represents an invitation to enter an information space or office task. An activity landscape is part mental construct and part physical; it is the space users interactively construct out of the resources they find when trying to accomplish a task.. A coordinating mechanism is an artifact, such as a schedule, or clock, or an environmental structure such as the layout of papers to be signed, which helps a user manage the complexity of his task. Using these three concepts we can abstract away from many of the surface attributes of work context and define the deep structure of a setting – the invariant structure that many office settings share. A long term challenge for context-aware computing is to operationalize these analytic concepts.

Contents

2. The deep structure of context

3. Office contexts are complex ecologies

What constitutes work context and how should it be represented? Consider an office. Offices are niches we inhabit and construct. Owing to our interactions over time we build up a system of supports, scaffolds, at-hand resources, reminders and interactive strategies that help us to perform our tasks, cope with overload, and recover from interruption. When people enter our office we have a collection of physical and symbolic resources, such as whiteboards, corkboards, schedules, email, post’its, day planners, speakerphones, videoteleconference units, desks, sheet paper, and of course, computers to facilitate discussion, coordinate our activity, and record outcomes. At any moment, the state of these resources sets the arena for the next round of activities. Their physical layout and their state partly constitutes the current context of work. How shall we represent this complex contextual state?

Context can be understood at many levels. As Dey, Salver, and Abowd (2001 [this special issue]) have emphasized, the first step is to ground the notion in directly observable or readily discoverable elements of the environment. These elements include the location and identity of people and objects, their activity status (tired, hot, noisy), the general activity they are involved in, such as reading, attending a meeting, and the time period they are in a location, and engaged in an activity. Working from these, and using background knowledge and the history of environmental changes, it should be possible to infer more complex descriptions of context. This is surely necessary. Context is a highly structured amalgam of informational, physical, and conceptual resources that go beyond the simple facts of who or what is where, when, to include the state of digital resources, people’s concepts and mental state, task state, social relations and the local work culture, to name a few ingredients. How these interact is not yet known.

The ultimate goal of ubiquitous and context aware computing will not be achieved until we have a theory of the interaction of these elements, and more particularly, an account of how we humans are dynamically embedded in this contextual nexus. The theory of distributed cognition has a special role to play in understanding this relationship. My objective in this paper is to investigate this more complex notion of context, especially the context we create in our workplace, and discuss the tangle of ideas it is linked with.

2. The deep structure of context

The thesis to be presented here is that there is a deep structure to well used workspaces. Any venue that has been adapted to the ongoing workflow needs of a user will support those task specific needs by providing an underlying structure, or context for that work. With the right analytic tools and concepts we can discover this deep structure. A long term challenge for context-aware computing is to operationalize these analytic concepts and tools.

If this thesis is true it ought to be possible, in principle, to create a “portable office”. A portable office is a digital projection of the deep structure of a specific (momentary) work context. It is a digitally enhanced space where the relevant affordances of a referent office are recreated. In the ideal case, a user with an up to date portable office could move from physical office to office and pick up where he or she last left off. From a theoretical perspective this means that, at any given moment, an office has a deep structure, an underlying system of states, structures, and relations, that can be manifest in offices with different surface features. Accordingly, we must be able to represent these states, structures and relations which define the momentary deep context of work and then adapt and project them onto new venues.

Scenario. To ground the discussion, here is a simple scenario of how a portable office might work Spotted around the floor of a modern building in California are a variety of enclosures or ‘microvenues’ supporting wall displays, telepresence, easy scanning and printing of paper, and diverse ways of interacting with the digital devices present. Ms. McEx lives in Washington and can readily telepresent and patch into Mr. Wyman’s portable space supported in the California building to collaborate on their new architectural project. Mr. Wyman has the paper plan of their project and is currently marking it up with pencil. McEx has been collecting data from websites on useful equipment and on design ideas described in books and websites. Together they need to annotate the architectural plan Wyman has by adding constraints introduced from McEx’s equipment list, and they want to brainstorm on some new possibilities. As they proceed, they also need to make a To Do list identifying the next steps that should be taken. Each person has a desk pushed up into the corner of their office where there are wall displays on the front and side walls. At 6PM EST they leave off their collaboration. Tomorrow, when they meet again, Mr. Wyman will probably be using one of the other microvenues in his building, and others may join him. These other microvenues support the same functionality but may be physically larger or smaller. If Wyman’s portable office is effective there should be minimal cost to shifting venues.

How plausible is this scenario? How much of a previously active work context can be recreated in a physically different venue? Clearly, physical differences in space and layout will have an impact on the perceived context. And clearly, there are limits to how much one can digitally augment and reshape a physical space. Yet how significant the cognitive impact of these perceived differences is, depends on a host of questions about the way cognition is distributed between agent, furniture and office resources.

For instance, how is information about the context of work stored on physical desks, office walls, whiteboards and shelves? What coordinating mechanisms do individuals and small groups rely on to synchronize activity, distribute tasks and activities and manage at hand resources? What critical elements of a work situation cue memory, making it likely that office users will recall why they left papers out, why folders are open, why there are certain marks on the whiteboards, and so on? All these questions point to aspects of the work context we need to understand.

To make a start at answering these questions we must rethink what an office is and how we relate to it.

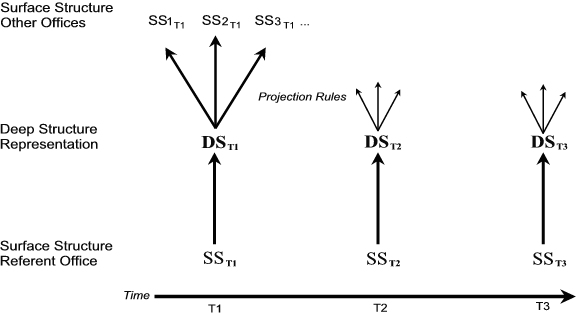

Figure 1. What must be present in different environments to ensure equivalent performance on a task? From a theoretical perspective this question requires identifying the abstract elements that constitute task context. Here we see a referent office undergoing changes as it’s owner makes progress on his tasks. Corresponding to surface changes of the referent office there are, at times, changes to the momentary deep structure of the current work context. These are represented in a time specific deep structure representation DSTi of the office. To support portability there must be projection rules from deep to surface structure SSTi which explain how to adapt the surface structure of new offices so that they instantiate the deep structure.

3. Office contexts are complex ecologies

The first step in reconceptualizing offices is to view them as ecologies where office and inhabitant co-evolve. Ecological systems display what Maturana (1975,1980) called structural coupling: each component of the system has a causal influence on the other. In the biological world organisms interact with their environment and with other organisms, who, of course, also tend to be part of each other’s environment, the whole system of components being interdependent and interlocked. The result is a highly complex system displaying attractors, instabilities and cycles typical of dynamical systems.

It is not hard to find examples of office-owner dynamics that display structural coupling. Most offices, for instance, tend toward a steady state of clutter during the different phases of activity, with the owners of the office evolving certain interactive strategies of trashing papers, filing folders, searching through piles, displaying reminders, posting stick’ems and so forth, which maintain an average level of disarray or structural complexity for each phase. The opening phase of a task is less cluttered than the mid phase, and upon completion there is typically a clean up. Change the furniture layout or take away the post’its and in tray, regardless of phase, and the owner’s maintenance and coordinative strategies will adapt. The consequence of the owner adapting to his or her office is that the office too is adapted, so that the two – office and owner – move through an interlocked history of structural adaptations.

In calling an agent and office a dynamical system we invite questions about the states this system moves through. Do we have a formal or quantitative transfer function? Are all states measurable? If so, we have reason to hope for a nicely operational definition of context.

Unfortunately, with the possible exception of structural complexity, it is unlikely that there are physically measurable features of the environment that highlight the key structural elements of an office that explain the dynamics of worker office interaction. The regularities we need are more qualitative: movement of information, number and arrangement of ‘entry points’, state of coordinative structures, shape of the activity landscape. These are the type of abstract characterizations of work context that are likely to be of greatest value.

In previous efforts to describe the state of an office, concepts like: reminders, placeholders, triggers, markers, constraints, annotations have been used. Notes or To-Do lists seem to behave as reminders of jobs to be done or appointments to be kept; an open folder acts as a placeholder indicating where one is in a task; a ‘sign here’ sticker placed on a sheet appears to trigger a signature, or a post’it with a phone number may trigger a call; an underlined phrase seems to mark what is important, or a bookmark indicates the section to be read; a routing list serves to constrain who you consider passing a document to, and so on. These are specific mechanisms found in offices that help office inhabitants manage their job. For discussion of these see Dix (1998), Kirsh (1995), Kirsh (1999), Kirsh (2000).

Although these mechanisms are helpful, they do little, however, to determine the theoretical limits on office portability, and therefore little to probe what the deep structure of office context is. We can appreciate that a digitally recreated office must duplicate the reminders, placeholders, markers and triggers found in a referent office, but it would be helpful if we had a more abstract characterization of work context. Thus, although any adequate theory of work context should provide the basis for identifying elements in the environment which function like reminders, etc., our goal is to have a more general theory which describes such elements in more abstract terms.

This is a tall order. The challenge in seeing an office as an ecology where inhabitants are structurally coupled to a more abstract structure – the deep structure of their work context – is that this deep structure must have the right psychological properties for inhabitants to act appropriately. It will not do to say that office1 and office2 embody the same deep structure, the same ecology, if they are so different in surface attributes that inhabitants of office1 are unable to continue working in office2 because they can’t recognize the cues they rely on to help them manage their activity. For instance, changes in the location, color, size, and shape of a clock in office1 and 2, at some point, may become significant enough that the coordinative power which the clock exercises in office1 is lost in office2. At that point office2 has failed to implement the deep structure of office1. So although the deep structure we are looking for is an abstraction, it must also be psychologically accessible. Even if the look of office2 is somewhat different than office1, its feel should be similar.

It is my view that the key components of office deep structure that can be translated into a psychologically accessible surface structure are entry points, coordinative structures, the shape of activity spaces, and of course, the actual information resources available in an office. This involves going substantially beyond what Dey et al. discuss.

Entry points are the first theoretical concept I will introduce that abstracts away from superficial attributes of a setting. An entry point is a structure or cue that represents an invitation to do something – to enter into a new venue or information space. In newspapers and web sites the information layout provides entry points for reading, scanning and following (clicking). For instance, in newspapers there are columns, pictures, figures, tables, and so on. Each title, each new well demarcated structure, beckons the reader to start their reading there. Because each heading, table, or caption is relatively small and identifies a relatively self contained article it is possible for a reader to review a newspaper page and make a rational choice of where to begin. Indeed, an effective reader may scan many entry points, picking up as much metadata and ‘information scent’ as is necessary to obtain a high level conception of what is in today’s news, and so develop a rough plan for moving through this information landscape. Well authored entry points make it easy to scan a paper and maximize the user’s reading experience.

In offices it is equally instructive to ask about the entry points which a given distribution of resources provides. We do not expect an office to be as well laid out as a newspaper, although some offices are. Rather, users, in the course of working in their offices, create a collection of entry points, invitations to revisit work threads. For example, an open email application invites us to do our email, the paper sitting on top of the input tray invites attending to the task it represents, an open day planner encourages us to review our schedule and to do list, while the open folder on our desk encourages us to return to the task linked to that folder. The telephone invites calling or attending to voice mail. Entry points, like affordances, are invitations to do things, typically information or communication related things. And, as with newspapers, we expect that an effective office dweller, when returning to the office, will scan entry points, pick up as much metadata and ‘information scent’ as is necessary to obtain a high level conception of what is ‘on call’, and so develop a rough plan – often in conjunction with planners, and lists – for moving through his or her activity landscape.

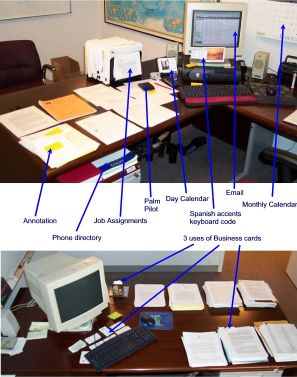

Figure 2. Here we see two structured desks, both more neat than scruffy, that support a similar idea to the entry points found in newspapers. The visual attractors which serve to draw attention to information entry points in an office are the characteristic shape and color of folders, envelopes, books and planners, the well planned layout of piles or business cards, the post’its labeling stacks, the vertical orientation of lists, and, of course, the brightness of one’s computer screen. After a break, or first thing in the morning, a user scans the desk, glances at the topics of a few entry points and using memory of the work related implications of each pile, begins to structure an activity path for the next period of time.

Users have very different preferences and tolerance for the number and type of entry points in their offices. Those of us with messy desks, for instance, are accustomed to many entry points, often in considerable disarray. Those of us with tidy desks prefer fewer entry points, each in a standardized place, and tidied up at the end of the day. These psychological preferences, which we may call neat vs. scruffy following an AI tradition, carry with them different costs and benefits, leading each personality type to prefer their own method of organizing office space.

For neats, the virtue of a tidy desk and office is that it structures entry points to canonical locations. Need information about a task? Is it still pending? Go to the pending tray. Is it completed or mostly completed? Go to the filing cabinet. Assuming it is possible to categorize one’s informational goals in terms of one’s existing filing scheme, it is easy for a neat to figure out where to look to find the entry point for sought for information.

Neats also differ from scruffies in the way they tend to use entry points to help start their office day.[i] When a paradigmatic neat enters the office in the morning, he or she typically finds a desk and office with a smallish number of folders or papers in piles, a relatively clean space beside the computer and any folders that have been left out from the day before are, more often than not, closed. Neats stabilize their environment before they leave for the day. This regular maintenance and stabilizing behavior is a major behavioral feature that characterizes a neat. But then, because there are few entry points to attract a neat in the morning, fewer placeholders, reminders, triggers and markers hanging around, neats typically make use of explicit coordinating structures such as lists, day planners, the order of documents in their in tray, to determine their initial activity. According to our pilot data, their day tends to be more scheduled than scruffies because it is more planned and less data driven by the attractors in the environment.

For scruffies, by contrast, a tidy office provides too little direction. The virtue of a messy office, from a scruffy’s viewpoint, is that it can hold large amounts of information about activities. Trivially this is true. According to the theory of descriptive complexity the more random a structure the more information it can encode; the greater the disarray the greater the amount of information it can store. Of course, this is not what a scruffy means. Their claim is typically that the simple categorization schemes used in most filing systems, such as alphabetical ordering by author or title, or chronological ordering by recency, do not do justice to the dynamic needs of activity. One reason paper accumulates into piles on a messy desk, then, is that scruffies dislike the strictures of standard filing systems. They avoid filing. And indeed, the categories that best describe the piles of files that build up over time on a messy desk are not found in the library of congress subject catalogue or anywhere else. They are ad hoc categories. We need to understand these categories if we are to represent the structure and work context of desks.

Ad hoc categories are non-standard classification categories that are constructed in the service of a task. Unlike most categories, which are based on some degree of feature overlap (including functional features), an ad hoc category is one that need have no significant feature overlap. For example, objects as diverse as children, money, and photo-albums may be assigned to the same category, in this case the ad hoc category of “things to take out of the house in the case of fire” (Barsalou1983). Such ad hoc categories are created as needed, they bind or unify a set of otherwise disparate elements that are meaningful to the agent because of his or her current activity.

When looking for a meaningful category that unifies the papers in a pile, there is often no category other than an ad hoc one. Scruffies seem to make abundant use of ad hoc categories and so pose a challenge to those of us trying to represent their work context. Moreover, the more piles there are, typically, the more likely it is that some files span several piles. This could be ignored if it were not semantically informative. But again it seems that pile spanning is intentional; it is a way of multiply indexing or cross classifying documents. In such cases, a document that is relevant to both activity1 and activity2 may be laid horizontally so that it is in two piles.

Despite the abundance of meaning in their environments, or perhaps because of it, scruffies pay a cost in terms of search time for the profusion and imprecision of their entry points. Since information is scattered, it is harder to find all of it. Users cannot know whether partly completed tasks are in the pending tray, the input tray, or on the table. At times it can take so long to find sought for information that it is effectively lost. Although scruffies regularly avow in interview that they know where everything is, and that their office only seems to be in disarray, observation has shown that there is inadequate order and clarity to their entry points to make it easy to reliably predict where information is to be found.

Yet even this negative often has a compensating factor. In the best case, the chance for opportunistic discovery of useful information offsets the costs of excess search time. Opportunism in this context refers to the act of noticing opportunities for advancing goals that are not currently on one’s goal stack. A simple example typical of the AI planning field is setting out to the supermarket with the goal of buying a lamb chop for dinner and changing dinner plans at the supermarket because of a great sale on salmon. The goals that should be active at the supermarket define a relevance function that should have nothing to do with fish. But street wise shoppers are always on the lookout for bargains for tonight’s dinner regardless of what their plans were when they set out. Hence their shift to salmon when they should have been buying lamb.

In the office environment the greater the number of entry points the greater the chance that looking for information needed for one task will prove useful for another task not currently in the immediate goal stack. As we will discuss in the next section, an office environment supports many activity spaces, each with its own set of entry points. Since scruffies are more likely to keep entry points of other tasks around, invariably with less than clear demarcation between them, there is a higher chance of accidentally stumbling on material useful to task2 when looking for material useful for task1. If the scruffy is a very data driven type of person this will often cause a shift in activity from task1 to task2.

Opportunism in the office can also apply to task1 as well. If there are many piles distributed on a desk, there is also a better chance of opportunistically discovering information relevant to the current task (task1). We can expect this improvement in likelihood because the pile containing a target document embodies a categorization principle which raises the a priori probability of additional documents also being relevant. Thus it is not surprising that as a scruffy rifles through a pile of files looking for a document he recalls placing somewhere in it he may stumble across another document – one he did not have in mind for this project – that is also relevant.

I have been arguing that entry points are a useful abstraction for representing an important aspect of the office work context. Yet beyond what I have said about individual differences in the number, crispness, and distribution of entry points found in offices what more can be said about how to represent entry points? Can we characterize the factors which bias how people react to entry points disbursed around an office? These are an important component of the context of work for they influence how people behave.

A first start at an analysis of entry points begins with the key dimensions along which they vary. Below are six such dimensions. Four are ‘objective’ or user independent dimensions, two more are ‘subjective’ or user relative.

The four objective dimensions are:

· intrusiveness – how attention getting are the cues indicating an entry point? Post’its are yellow, business cards have a characteristic shape and paper quality, planners are leather or textured, but none of these have quite the attention getting power of ringing telephones, the pulsing lights of answering machines, the knock of a colleague or the opening of a door. Intrusiveness measures how visually or sensorially attractive an entry point is, and helps to determine the a priori probability that a user will approach that entry point.

· metadata rich – how much information is there about what we will find once we enter an entry point? Folders have labels or descriptive stick’ems, papers in in-trays have large type headings, headlines are descriptive, pictures support quick glances, books have evocative jackets. Even the pile itself displays metadata since it is the embodiment of an ad hoc category. The more metadata available on an entry point the less memory is required when a user begins to plan the next phase of activity, and the fewer documents need to be searched when a user is looking through piles.

· visibility – how distinct or unobstructed are the entry points? My to do list is open to today, conference invitations posted on corkboards are partly occluded by other papers, windows on computers are minimized so there is only a simple link, web page links are either below the fold or ‘directly’ visible. Most entry points in an office are invisible because they are stored away in filing cabinets. Others are not clearly identified because of pile merging or multiple pile spanning. Prima facie, the more visible an entry point the greater its chance of being used.

· freshness – when was this file, stick’em, note on the whiteboard created, placed, last touched? Recency influences recall and so increases the likelihood that a document will be retrieved for use in a current activity.

The two subjective dimensions are:

· importance – how pressing is the activity or information associated with the entry point? Letters requesting action typically have a due date and an importance level in a user’s to do list. Importance increases as the due date nears; drops once the due date passes. Importance influences probability of use.

·

relevance to current activity – how useful would

it be to explore the path marked by the entry point given what I am currently

doing? Any significant activity opens

many threads, creating a relevance metric that ties different resources

together for a given user (and task).

Prima facie the more relevant an entry point, other things being equal,

the higher the probability it will be consulted.

Understanding how to characterize entry points is one step toward improving our representation of work context. It improves our ability to predict user behavior.

Activity landscape is the second concept that helps us understand the abstract structure of the work context. It is a major factor in shaping the behavior and ecology of an office. Just as entry points accumulate in physical offices, so do activity landscapes. An office can never be conceived as the embodiment of a single activity landscape: it is the result of a superposition of landscapes, each landscape with its own set of entry points, own set of values and own set of relevant resources.

The notion of an ‘activity landscape’ is a revamp of the original idea of a task environment, introduced by Simon and Newell. [1972] . Like a task environment we can think of an activity landscape as lying at the interface of user, task, and world. From the user comes the concepts and categories that carve the physical world up into activity meaningful parts. From the task comes constraints (but now soft constraints) on whether an action is relevant and how worthwhile it is; and from the world comes the underlying support for activities and the causal basis for the consequences which actions have. An activity landscape is the construct resulting from users projecting structure onto the world, creating structure by their actions, and evaluating outcomes. It is the theoretical structure in which to track and analyze the goal directed activity of a user.

The context of work is tied up intimately with the concept of an activity landscape. The schematic structure which workers project helps to shape how they proceed. They see a collection of resources as relevant to their work. This projected structure – this notion of being relevant – goes beyond recognizing temporal dependencies and logical ordering. It includes ideas of ‘how things are done’ owing to corporate culture. It includes ideas of how to use resources or scaffolds to do a better job. Work unfolds in an activity landscape because activity landscape is the term we give to the structured environment in which specific work tasks unfold. The two are analytically linked. Too bad the concept of an activity landscape is still ill defined.

There are several reasons why activity landscape resists precise definition. First, activities are open ended processes. For example, in writing a back to office report, what are the component tasks and sub tasks involved? Formally the task can be broken down into a subgoal structure, the logical and temporal ordering of the task. Yet when close attention is paid to people’s actual behavior it is evident that people do many things that are relevant to writing the report but which do not fall into the normal conception of a subgoal. For instance, before I begin to write such reports I typically check my schedule to see if I will be interrupted. This is not a predictable subgoal. It is rational for a person who must manage multiple tasks, but it is outside the normal construal of a subtask of writing. It seems more of a preparatory move. Similarly, I may have a habit of sharpening or chewing a pencil before I begin – even if I no longer use pencils in writing reports. Habits and ancillary actions such as maintenance actions, preparatory actions, trashing activity, exploratory actions, dropping reminders, and more may be actions somehow associated with an activity, but which fall outside the concept of an action that is directly relevant to a goal. This is one reason activity landscape is hard to define.

Second, activities, unlike moves in a task environment, should not be understood as a collection of discrete actions taking place at environmentally defined choice points. Often what is of most interest in an activity is the way agent and environment are tightly coupled, as in car driving, or pencil sharpening. Admittedly, it is fair to say that most information oriented tasks can be discretized to some degree: searching a website for information, or hunting through one’s filing system for a document, can both be decomposed to a network of choices and decisions. But often when scaffolds and supports are used to help one search there is a dense pattern of interaction that is not well characterized as a trajectory of decisions over choice points.

Third, and perhaps most importantly of all, activity landscapes are hard to individuate. At any moment, the appearance of an office is likely to be the consequence of multitasking. Interruptions are constant, requirements change, and new demands are made before all old ones are discharged. In ideal cases, different entry points are associated with different tasks. But in the case of scruffies, entry points are seldom so disciplined. The same entry point may lead to information resources relevant to several tasks. It is one thing to observe an agent in action and infer the boundaries of his activity space so far; it is another to infer the possible bounds of that activity landscape . Because of the constant cross over and opportunistic use of resources it is rarely possible to circumscribe an activity landscape, or a resource space, to a tightly demarcated system of resources.

And yet sharpening the definition of an activity landscape is just what we must do if we are to make precise the concept of work context. Because we perform dozens of activities and tasks in our offices the office landscape is inevitably an overlay of many activity landscapes. Given the interaction between these layers they cannot be linearly separable. So the hope of definitively isolating the separate contributions each landscape makes is not likely to be realized. Yet perfect separability is not necessary for a first approximation. Since most users periodically tidy their office precisely to unclutter their workspace with what is essentially detritus from other activities, there remains a workable notion of all and only the right elements required for a particular context of work. This involves deconstructing the context, understanding the ad hoc categories which the agent projects onto the activity space. It is a tall order, but an inescapable part of the abstract structure we are trying to discover.

The last basic concept we will consider is coordination, and the mechanisms which facilitate coordination. The idea of coordination is that agents partner with the resources in their environment when they work toward completion of a task. When I leave a post’it on my computer monitor to remind me to pick up the dry cleaning, I am relying on the post’it being there, and relying on my regular noticing of such reminders, to help me achieve one of my goals. The post’it serves as a coordinating device. Without such an external device I would need an alternative method to backup my memory. Although it is an odd way of speaking, the post’it and I are partners in getting me to my goal.

Any adequate representation of work context must include information about the state of different coordinative mechanisms in that context because they play such an essential role in the successful action of an office worker. How could a neat get through the day without making a list, consulting his or her daytimer, schedule, appointment calendar, or clock? How could a scruffy get through the day without annotating paper, dropping reminders, markers, placeholders? All these resources figure in an agent’s coordination with their environment.

To get a feel for the idea of coordination being advanced here consider the role which clocks, fasteners, containers and forms play in a standard office. Clocks play the most obvious role: they facilitate temporal coordination between different people, and they help an individual person pace him or herself as they work. Without clocks how would we know when to show up at a meeting, when to leave? Clocks allow us to synchronize our actions. At an individual level clocks let us keep an eye on how far off our deadline is. An essential part of managing a project is to break it down into logical sub components and then to map these onto a timeline. Without a calendar or clock to convert this abstract mapping into here and now directives to action, we would fall off track, running behind our obligations or pointlessly running ahead. Short of relying on other people to tell us the time, time management is not possible without a clock. Clocks figure deeply in self coordination. Their presence, in easy view, is an important part of the work context.

Containers and fasteners also serve as coordinating mechanisms. In almost every office there are fasteners such as staples and paper clips, and containers such as trays, drawers, folders, envelopes, and so on. The role of fasteners as coordinating tools is often overlooked. Yet staples and paper clips allow users to link individual pieces of paper into a modular group that can be passed around. They coordinate separate sheets by mechanically keeping them together. This saves search, it improves filing and it improves tidiness. It also defines an entry point. Folders, trays and large envelopes serve a similar function but are regularly used for papers that accumulate over a longer period of time and which are often destined for a drawer or filing cabinet., A folder can go directly from tabletop to cabinet because folders have been designed to a standard size. This is not true for clipped papers. Fasteners and containers, too, are part of the work context.

Forms are another powerful coordinating mechanism in workplaces. A form is a structured set of questions or options that must be filled in and then passed on. Forms for routing documents through a circulation list or authorization chain are popular in paper heavy offices. They tell the reader to tick their name off and pass it on to the next person on the list. The value of such forms is that they constrain the actions a user need consider. They serve as instructions, another coordinating mechanism. Moreover, by linking the form to a single physical document, a form on an authorization list serves the secondary function of keeping in one place all the signatures that are required for an authorization. It both coordinates decisions and reduces effort. Well designed forms are one of the more powerful coordinating devices in an office. They are part of the work context.

To say that clocks, fasteners, containers and forms are part of the context of work is somewhat misleading. It is because of the way they figure in structuring the environment that they constitute context. This agent-artifact coordination is not too hard to understand for most of these artifacts, but there are other coordinative mechanisms that are far more intricate.

To appreciate the complexities here consider the way project management information is distributed around an office. On the explicit side, there are dozens of office devices intended to help us stay on task. Day planners, to do lists, check lists, schedules, appointment calendars, alarms, reminders, and more are the stock in trade of office supply shops. These artifacts are modified by office inhabitants and participate in a coordinating loop where the agent changes the state of the artifact, the artifact prompts the agent to act, and so on. Business culture has developed a collection of representational elements and interactive strategies to structure thought and action. Users are taught to tick off tasks when done, they are shown how to list and prioritize tasks, they learn themselves to leave post’its and highlight sections as annotations and reminders, and they soon rely on the contents of the whiteboard to keep fractional state of previous conversations and plans (hopefully enough to allow reconstruction by the authors). They use corkboards, taped papers on the wall, and phone lists to store long term reminders.

When information about a task can be associated with definite regions, or with definite devices in an office, we will call it locally stored. The input trays, to do lists, and whiteboards, just mentioned, store information locally. Fasteners, containers and forms help to store information locally. In principle, we can track the state of these devices and incorporate them as part of our representation of office deep structure.

But locally stored information is only a fraction of all the information in office. Incorporating the state of task information distributed more globally in an office is more difficult. When information is encoded in spatial arrangements, and in the collective state of many resources, we will call it globally stored. Information that is globally stored normally has to do with ‘where’ one is in a task, not in the sense of ‘you are half way through’, but rather in the sense of ‘this is the current state of your task’, so that if interrupted you may be able to recover your train of thought and activity by looking around.

It is convenient to think of performance of a task as defining a trajectory of state changes. Hence the idea of a task having a current state. Yet what do each of those states on the trajectory look like? For instance, in writing a one page memo, completion of the task may require telephoning people, reading emails, consulting references and previous memos, taking and redacting notes, and thinking and composing on the computer. Part of the state is found in the current computer draft. But it is also found in the progress made on the various sub-tasks – the notes recorded from completed calls, the email that has been read and distilled, the papers in the folder opened on the topic, and so on. All these resources affiliated with the overall task figure in the global state of the task. And that is before we consider information in people’s memory, and information that must be inferred from the strategies they have evolved. The global state is the collective state of these sub-tasks plus their structural relations. It is a distributed state.

How might we represent this distributed state? Certainly tracking the nature and location of entry points is useful. So is identifying the activity space of the task. But there are additional factors concerning the cost structure of the activity space owing to the physical layout of resources which may serve to attract, repel or constrain activity, and organizationally wise actions such as screening out unnecessary documents before they become visible entry points that make the story more complex.

There is much theoretical work to be done before we understand the way users interact with coordinating mechanisms. But we cannot hope to understand the influences shaping a workers activity without a proper study of the coordinating mechanisms they rely on. The nature, location and way users count on these mechanisms is an integral part of the context of work. It is a further reason why understanding work context lies outside the reach of simple models of who, what, where, when and how.

I have been describing the context of work as a highly structured amalgam of informational, physical, and conceptual resources that go beyond the simple facts of who or what is where, when. Some of these resources are shared knowledge between participants, others have to do with the structure of the tasks a user is involved in and the different ways he or she has of coordinating the use of physical, informational and conceptual resources between himself, the work setting, and teammates. Many of these resources could in principle be abstracted from their customary embodiment in a particular physical place, thereby creating a more abstract structure which could be re-implemented in different physical venues. Although the goal of creating a portable office will not be realized anytime soon, the analytic work necessary to understand this structure is an extension of current work on situated and distributed cognition.

I argued that research must push deeper in three directions if we are ever to disentangle the notion of context required to support this more abstract conception of our work setting. First, we must understand the factors which bias how people react to rich information spaces, loaded with entry points to more information. Second, we must unravel the complexities of the activity landscapes we interactively construct out of the resources we find and the tasks we have to perform. Finally, we must chart the diverse ways people coordinate their activity with their environment and with others. Concepts like these represent the next step in our understanding of how humans are coupled with their environments. They will help us illuminate the everyday mysteries of our context of work.

Acknowledgments. I would like to thank my colleagues Aaron Cicourel, Ed Hutchins, and Dan Bauer for valuable conversations about coordination and activity spaces.

Support. The author gratefully acknowledges support for research on this and related topics by the National Science Foundation (KDI grant IIS 9873156).

Authors’ Present Addresses. David Kirsh, Dept of Cognitive Science, UCSD, La Jolla, CA 92093-0515.

HCI Editorial Record. (supplied by Editor)

Barsalou, L.W. (1983). Ad hoc categories. Memory and Cognition, 11,

211-217.

Dey, A. K., Salber, D., Abowd, G. D. (2001).

A conceptual framework and a toolkit for supporting the rapid prototyping of

context-aware applications. Human-Computer Interaction, 16, xxx-xxx.

Dix A, Wilkinson, J., Ramduny D. (1998).

Redefining Organisational Memory - Artifacts, and the Distribution and

Coordination of Work. Workshop on Understanding work and designing

artefacts, York, 21st September 1998. Extended

abstract at http://www.hiraeth.com/alan/papers/artefacts98/

Kirsh, D. (1995). The Intelligent Use of Space. Artificial Intelligence. 73, 31-68.

Kirsh, D. (1999). Distributed Cognition, Coordination

and Environment Design, Proceedings of the European conference on Cognitive

Science. 1-10.

Kirsh, D. (2000). A Few Thoughts on Cognitive

Overload, Intellectica, CNRS. 30, 19-51. Also available at http://icl-server.ucsd.edu/~kirsh/Articles/Overload/published.html

Maturana H.R. (1975) The organization of the

living: a theory of the living organization. International. J. of Man-Machine Studies 7: 313-332

Maturana. H.R. Biology of cognition. In F. Varela and H. Maturana (eds.),

Autopoiesis and Cognition. Reidel, London, 1980

Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon, Human Problem Solving

(Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, 1972).

Smith, S.M., Glenberg, A.M., & Bjork,

R.A. (1978). Environmental context and human memory. Memory and Cognition, 6,

342-353.

Tulving, E. & Thomson, D.M. (1973).

Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychological

Review, 80, 352-373.

[1]

The basis for these comments on neats vs. scruffies is an unpublished pilot

study I have undertaken of five offices having two neats two scruffies and one

person who is not so easily categorized.